Move the Chains

This article uses the idea of a “first down celly” to explain why sports language shows up everywhere and what it reveals about how men learn to handle emotion.

Nuri Robinson

1/8/20263 min read

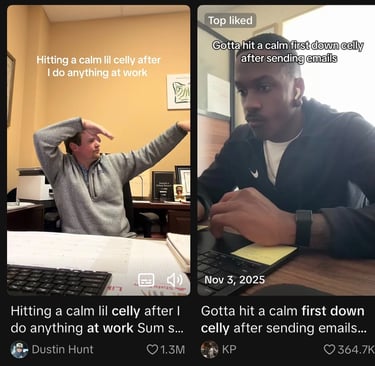

People will hit a “first down celly” when they finish a task, or say “ball up top” when something goes wrong and it’s time to move on. You hear it at work, in school, on social media, a lot of times from people who haven’t played organized sports in years, or never really did. Most of the time, it gets written off as a joke, but I wanted to think about why this is so prevalent. Because things like this don’t stick around unless people actually relate to them.

These symbols convey a way of understanding progress, failure, and emotion that a lot of people don’t get anywhere else. And I believe what’s traveling with the language isn’t just slang, it’s structure, and at the center of that structure is sports, doing way more cultural work than we give it credit for.

Sports end up being one of the few places where big emotions are not only allowed, but expected and encouraged. Excitement, anger, frustration, and pride are all emotions you can show without having to explain yourself. There are rules for how it comes out, but the feeling itself isn’t treated like a problem. You can yell, celebrate, sulk for a moment, then get back in the huddle. Nobody asks you to explain yourself. Nobody asks you to be “more emotionally articulate.” You’re just in it. And this matters, especially for men.

Sociologist R.W. Connell would say that masculinity is a social system with rules about control, competence, and emotional restraint. Certain emotions are acceptable as long as they look purposeful. Others carry risk. Losing control in the wrong setting can cost you status, credibility, or belonging. Sports actually reorganize these rules.

Inside a game, emotion is legitimate as long as it’s tied to effort, performance, or loyalty to the group. Anger becomes intensity, anxiety becomes focus, and disappointment becomes fuel. The emotion isn’t the point; it’s the function. That’s why this works; you’re allowed to feel deeply without having to step outside what masculinity already recognizes as acceptable.

The structure of sports makes this possible. Everything is bound. There are rules, a clock, and there’s always a next play. Failure is visible, but temporary. A mistake doesn’t define you; your response does. That logic creates an environment where emotion doesn’t spiral or stick. It moves, and it’s fluid, something that never feels permanent; even in the worst of situations, you will always have next season.

That’s where the language comes in. “Ball up top,” “I just gotta lock in,” “Bad day to be a spreadsheet.” In a game, these are emotional resets. They acknowledge something happened without dragging it out or assigning blame. When they move into everyday life, they do the same thing. Saying “ball up top” after a mistake at work isn’t about ignoring what happened. It’s about signaling that the moment has passed, that you still belong, and that there’s another rep coming.

To this point, a guy named George Lakoff (Sociologist) would say that metaphors don’t just decorate language, they shape how people think and act. Sports metaphors turn abstract experiences like progress, failure, and pressure into concrete, familiar terms. A “first down” is progress without pretending the job is done. It gives people permission to feel good about momentum in systems where success doesn’t have a clear scoreboard. These metaphors make life legible, reduce ambiguity, and tell you how to feel.

At the same time, that structure has limits. Sports favor action and forward progress. That’s great for resilience, but it can also encourage people to close the emotional loop too quickly. Not everything needs a reset. Some things don’t fit neatly into a “next play” framework; there are experiences that just need time and stillness. So the concern that comes up isn’t that sports are used as emotional tools. It's what if these tools can become the only ones available.

Sports function as emotional infrastructure. They provide shared rules, rituals, and language for handling pressure, failure, and intensity in ways that feel legitimate. The reason sports metaphors travel so well is because they solve a real problem: how to feel without losing face. So when someone hits a “first down celly” at work, or tells you “ball up top” after a rough moment, it’s not random. It’s people reaching for a system they trust to manage emotions they were never really taught how to handle elsewhere.

Directly after writing this, I hit the meanest TD celly you’ve ever seen… Trust me, bro it was tuff